Animated Turtle Graphics using PDF

Implementing a turtle graphics system in HexaPDF

After seeing one of Jamis Buck’s weekly programming challenges being the implementation of a turtle graphics system, I decided to tackle this one using HexaPDF as backend.

First I will introduce the basics of turtle graphics. Then I will show you how a simple implementation using HexaPDF looks like and some examples. After that it’s show time - (ab)using the presentation capabilities of PDF to animate the turtle graphics!

Turtle Graphics Basics

If you are not familiar with turtle graphics, here is a short primer:

- There is a turtle which has an initial position and heading.

- It can move a given number of steps forward or backwards.

- It can turn a given number of degrees to the left or right.

- It can move with or without drawing a line.

The turtle follows the instructions that you give and draws an image consisting of lines as a result. That’s it!

There can also be additional instructions like changing the width or color of the drawn lines but they are not necessary for the basic turtle graphics.

Implementation Using HexaPDF

When you look at a PDF in a viewer, you will find that it can contain vector graphics besides raster graphics and text on a page. Not everything is built-in, though. For example, there are no native instructions for drawing circles, they have to be approximated using Bézier curves.

However, for the turtle graphics I only need to be able to draw lines and there are native PDF instructions for them. HexaPDF has a Canvas class that provides access to all these PDF drawing instructions, so I chose it as backend for drawing.

One other design decision was that the given instructions should be recorded so that the turtle graphics can be used multiple times, either on the same PDF page or on different pages.

The implementation itself was straightforward (see below for comments):

require 'hexapdf'

class Turtle

Instruction = Struct.new(:operation, :arg) # (1)

def initialize

@instructions = []

@x = 0

@y = 0

end

def move(steps) # (2)

@instructions << Instruction.new(:move, steps)

self

end

def forward(steps) # (2)

move(steps)

end

def back(steps) # (2)

move(-steps)

end

def turn(degrees) # (2)

@instructions << Instruction.new(:turn, degrees)

self

end

def right(degrees) # (2)

turn(-degrees)

end

def left(degrees) # (2)

turn(degrees)

end

def pen(up_or_down) # (2)

@instructions << Instruction.new(:pen_down, up_or_down == :down)

self

end

def draw(canvas) # (3)

x = @x

y = @y

heading = 0

pen_down = true

canvas.move_to(x, y)

@instructions.each do |instruction|

case instruction.operation

when :move

x += Math.cos(heading) * instruction.arg * @scale

y += Math.sin(heading) * instruction.arg * @scale

if pen_down

canvas.line_to(x, y)

else

canvas.move_to(x, y)

end

when :turn

heading += Math::PI / 180.0 * instruction.arg

when :pen_down

pen_down = instruction.arg

else

raise ArgumentError, "Unsupported turtle graphics operation"

end

end

canvas.stroke

end

def self.configure(**kwargs) # (4)

new.configure(**kwargs)

end

def configure(x: nil, y: nil) # (4)

@x = x if x

@y = y if y

self

end

def create_pdf(width, height) # (5)

doc = HexaPDF::Document.new

page = doc.pages.add

page[:MediaBox] = [0, 0, width, height]

page.canvas.draw(self, x: width / 2.0, y: height / 2.0)

doc

end

end

HexaPDF::DefaultDocumentConfiguration['graphic_object.map'][:turtle] = 'Turtle' # (4)

Comments:

-

This is the struct for representing a single instruction.

-

The methods for moving, turning and putting the pen down or up are just adding instruction objects to the instruction list. Returning the turtle object allows chaining these methods together.

-

After the instructions have been recorded, they have to be played back on a canvas. This is done in the

#draw(canvas)method by iterating over the instructions and following them. -

The instance method

#configureis used to set the initial position of the turtle on the canvas.Together with the class method

::configureand the instance method#drawthe requirements for being a “graphic object” are fulfilled. Additionally, the turtle class is registered with HexaPDF so that it can be used on any canvas without knowing the actual class name. -

This convenience method returns a HexaPDF document containing a single page on which the turtle graphics have been drawn. The document can be modified if needed, or just written out using the

HexaPDF::Document#writemethod.

As can be seen implementing the basics is rather easy. I implemented several additional features later on, like setting the color and line width. The final implementation is available on Github.

Examples

Additionally to some examples written by myself, I took the three examples from Jamis Buck’s

solution (boxes.rb, circles.rb and spiral.rb) and adapted them for my implementation.

Here are the results (PDFs rendered as PNGs):

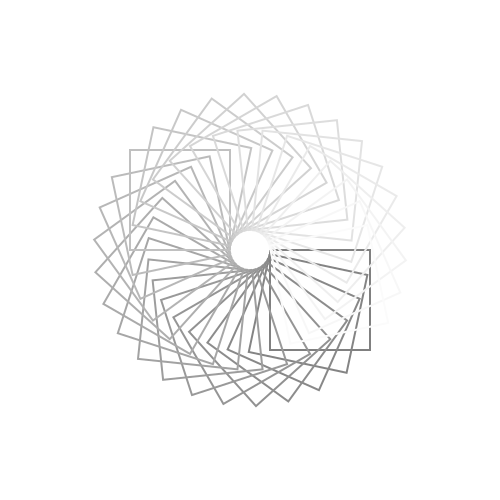

boxes.rb

circles.rb

spiral.rb

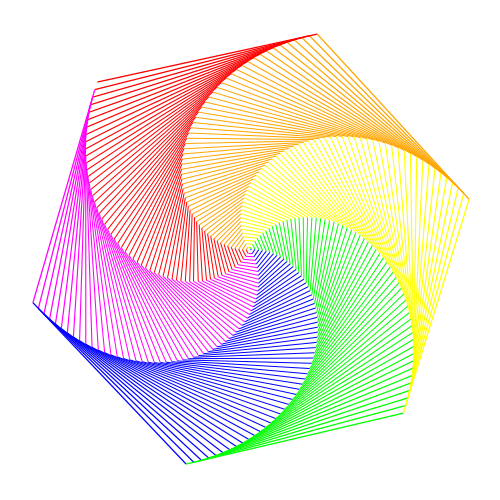

color-spiral.rb

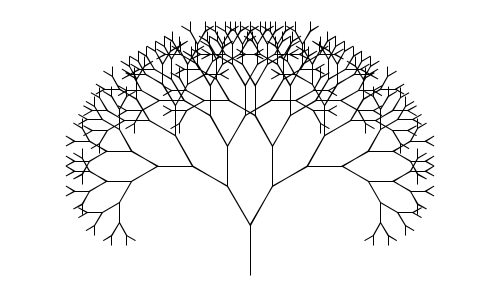

tree.rb

ruby.rb

Animating the Turtle Graphics

Now that we have an implementation and some example, we can come to the fun part: Animating the turtle graphics!

There are several ways to do animations in PDF. However, most of them are not well supported in viewers other than Adobe Reader:

-

The only way (as far as I know) to provide animations in PDF without invoking presentation mode is to use Javascript and widgets (see the animate LaTeX package as an example). However, this only works with Adobe Reader under Linux.

-

So we are left with (ab)using presentation mode for our animation.

PDF supports sub-page navigation where a presentation step doesn’t show the next page but does something else. This could be used, in conjunction with optional content groups (OCGs; think: layers), to show frame after frame for the animation. The benefit is that only a single page is needed. However, although OCGs are supported by most Linux PDF viewers (e.g. Okular and Evince), sub-page navigation is not, at least not together with OCGs.

-

This means that we have to use individual pages, one page for one frame of the animation.

The straightforward implementation would be to render the first frame on the first page, the first

and second frames on the second page, the first three frames on the third page and so on. But this

means that we have a complexity of O(n^2/2) time and space wise. Therefore this is not an ideal

solution.

My first though for remedying this situation was to use Form XObjects. This is a way in PDF to store repeated content, like a header, in a separate object and reuse it only several pages. For the animation we could store all frames in separate Form XObjects and then nest the form XObjects to get the desired result.

I.e. page 1 uses xobject 1 containing frame 1; page 2 uses xobject 2 containing a reference to xobject 1 and frame 2; page 3 uses xobject 3 containing a reference to xobject 2 and frame 3; and so on.

As it turns out, there is a limit on how deep Form XObjects can be nested. The limit for Adobe Reader seems to be about 30 nesting levels, Okular’s is at about 100. So this isn’t a general solution either.

What I settled for was using multiple content streams. In PDF page definitions are separate from the content streams. This means that multiple pages can refer to the same content stream and that a single page can refer to multiple content streams.

My implementation reuses an existing content stream every 10 frames. This means that the first page contains the first frame, the second page the first and second frames, …, up to the tenth page which contains the first ten frames. The eleventh page then just references the content stream with the first ten frames and uses another content stream with only the eleventh frame.

This means that the frames have to be iterated only once and that the needed space is also vastly

reduced. The implementation can be found in the #create_pdf_animation method.

Conclusion

First and foremost: Turtle graphics are fun! Really, they are! ☺

But besides being fun they are also useful for teaching programming to kids (Logo programming language anyone?) or visualizing Lindenmayer systems.

Implementing the basics was rather easy, especially when a capable backend for drawing is already available as was the case with HexaPDF. However, I was a bit disappointed to find out that a bit more advanced PDF functionality like sub-page navigation isn’t implemented in most Linux PDF viewers. There is a version of Adobe Reader available on Linux but its outdated and should not be used due to security vulnerabilities.

Lastly, I gave talk at vienna.rb last week on February 2nd on this topic which was quite well received. There is a video of a sample animation shown during the talk, complete with a moving turtle. The slides of the talk in PDF format were created with HexaPDF and the turtle graphics systems, showing off both of them.